Lost, by Hans-Ulrich Treichel, Random House

Lost, by Hans-Ulrich Treichel, Random HouseA boy's parents never get over the loss of their older son, whom they last saw while fleeing from the Russian army in 1945. There is virtually no dialogue, and the deliberately slow progress of the plot makes you anticipate a big finale that doesn't arrive. What you get instead is a paradoxical conclusion, that makes sense for the little boy if not for the other characters. This kind of "sober" narrative will surely get critical acclaim in academia, but it is also recommended to anyone attracted to the theme of the fragile nature of the human mind.

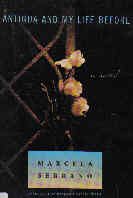

Antigua and My Life Before, by Marcela Serrano, Random House

Antigua and My Life Before, by Marcela Serrano, Random House

The day the Berlin Wall fell. Everything began that November 9, 1989, with the fall of the Wall. Who could have imagined how much more would come down with it. Which was what I told Violeta Dasinski that day. I ought to have been a witness: if only I'd paid more attention. In the photograph there is a forlornness in her expression I hadn't noticed until now. As if her consciousness were dissolving in her eyes. The date of the beginning of Violeta's public life was the day her name appeared on the front page of the Santiago newspapers: November 15, 1991. (Opening paragraph)

In the Wilderness, by Manuel Rivas, Overlook Press

In the Wilderness, by Manuel Rivas, Overlook Press

"There were three hundred crows.... and there was a girl and a church." The lady of the manor, Misia, accounts how the three hundred crows are poet-warriors of the last king of Galicia. A priest, Don Xil, explains to a young peasant, Rosa, that the paintings of beautiful women which are discovered on the walls of the church are sinful portraits. Rivas's "delicate, restrained magical realism, deploys Galician folklore to lend a mythic resonance" to a story about Spain's reluctant transformation to a modern urban lifestyle.

Michael Carroll

Michael Carroll